- Home

- Giorgio de Maria

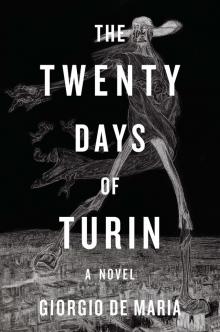

The Twenty Days of Turin Page 15

The Twenty Days of Turin Read online

Page 15

What happened next, when the frail membrane of suspense which had enclosed their coexistence like a shell finally burst, stirs me almost with horror to recount. It was another evening with the trio sitting at the customary table. Not one of them had as yet said a word. Only the candlesticks gave life to their three presences by the fidgeting of magnified shadows on the walls, and only the faraway slap-slap of lagoon waters breached the silence. Everything seemed to be unfolding just like the evening before, when the Straggler-Cat launched into a coughing fit that suggested he was about to make some trifling household discussion. Then, in an accent one would use for everyday table talk, he began to recite certain verses in Venetian. Marianna, who didn’t recognize these rhymes as her husband’s usual mediocrity, stood stiff like a gazelle that had heard roaring nearby. The poet too repeated the words to himself and turned pale. Watching them and pretending not to notice their shock, building more and more dramatic emphasis and almost relishing his intonation, the merchant continued the strophe he had started. Perhaps it was a gesture incited by fear, or perhaps the poet was ashamed, from hearing in such a slovenly recital the words he had long and fruitlessly pursued for his Manfred, enough that it roused him to grasp the end of his tablecloth and take cover behind it as if finding himself suddenly naked. Other words, other verses, piled on without pause, in somewhat garbled diction.

There is no telling, Your Eminence, if seeing an idea of one’s own—a personal notion one has not yet brought to full maturity—suddenly unveiled in a distorting mirror is an experience any man could endure. Few indeed have ever tried. But from what they say, it does not seem the Englishman took it well. The scene that followed, in fact, was a frenzy of paroxysmal movements. Some recount it as a wheezing chase around the table, where the merchant slurred verse after verse while the poet begged him in vain to put an end to the costly spillage; others say instead that the poet threw himself at the merchant in an instant and took him by the throat, hoping that this would arrest the grandiose flow of those words which had grown into a mighty cascade. I could scarce know which of the many versions told might be closest to infallible truth. But it seems the more probable to me that the merchant was able to escape his opponent’s grip and dwindle away from the room. Now the poet and his woman were very desperate to track him down. There are some who claim to have spotted the pair as they combed the streets that night, asking left and right if by chance anyone had seen him. And people even now recall their shallow breath, their fluttering hither and thither like moths around an oil lamp. When at last they found him, he was locked in a wine cellar inside the house and our poet had no choice left but to stop feebly and listen. From inside, the merchant’s voice poured out in abundance, oratorical one moment, hasty and monotonous the next. The Englishman tried beyond hope to take what he heard to memory and save some word or two. Rivers of poetry . . . unborn . . . prenascent . . . pelted through that door, perhaps vanishing without a second chance to be heard; nor was there a human shorthand swift enough to jot them down. All that night the poet stood there, to listen and to hear himself, with his hands outspread like a beggar. Only when dawn came again was he able to move and climb slowly back up the stairs, almost like a shade, sapped of all he had been.

At this you should ask, Your Eminence, how that husk of a man still happens to enthrall the masses, to sell poems and to be a prolific and celebrated wordsmith. If his whole store of rhymes and images had perished that night, then perhaps I wouldn’t worry myself too deeply over his destiny and the ruination his presence in the world even now serves to propagate. I would leave him to his fate, to chase whatever shallow death awaits him in some far-off land. But such is certain, however, that he has not remained entirely quiet, and that the lengthiest poems still jet out from his pen. You must be conscious of his Don Juan and of his Manfred, both taken skillfully to completion, and other works of his lately published to sizable admiration. It happens at times that men can outlive themselves and persevere, like wraiths, by carrying out the actions they have always carried out; their souls are mute but not their voices, and their hands and feet do not stop moving. Seeing them in the street or riding in the saddles of their chargers, no one would think that their minds had lost their hum, that the blood in their veins was heatless and spent; nor do the women they still hold tight to their bosoms ever imagine such a tremendous absence . . . And in the city there’s no lack of them . . . Often, even, the more the vacuum inside them is pierced, the more grandiosely they act, giving shows of themselves, fashioning great spectacles of gaiety, dauntlessness and brio. There’s never a Carnevale in Venice where their masks don’t make an appearance. And if times and manners continue to slide as they do now, it shall not be long before these walking husks will form great crowds, whose presence no one will be able to evade.

In the meantime, I can tell you that so far our Englishman hasn’t stopped making hasty and sporadic jaunts here in Venice. No one—at least, not anyone who isn’t in the know about his intimate secrets—would recognize him during these visits. Because Venice for him is a realm of humiliation, he hesitates to come here with his features so changed, like a leper who doesn’t wish to be pointed out. What could he still hope to do or find in this place, that he hasn’t done or gotten already? It’s painful to answer that kind of question. He does, at any rate, bring himself here, and after nightfall, he approaches the merchant’s house and knocks a number of times as a recognized signal. The door can be seen opening and the merchant leans out just a little; with a quick wave of his hand he bids his guest into the quiet of the house, where they both remain for a few short moments. So indeed it stipulates, the unsavory pact which binds them, and has bound them since that night. The Englishman divests himself of a bag of money; the merchant, a bag of parchment scrolls. What they discuss among themselves cannot be anything two mortals should ever say to each other in this life. Their sad haggling complete, the Englishman pulls away from the house and dissolves into the murk without breathing a word. Certainly, whatever is written on the scrolls could sound nothing like his mother tongue; but it serves him little to shed tears over so much infidelity if they nonetheless contain the works that ought to have been his. Arriving as he will at some outlying hostel, far from the inquisitive glances of his friends and the crowd, he will begin to unravel that priceless bundle at once. And then his pen shall stand ready to translate his verses from that humble dialect into his native English. Once that barren struggle comes to a close, others will undertake to publicize it and to entrust it to the wings of fame. Can it incite much wonder, then, that the Englishman’s assets continue to dwindle and his castle at Newstead is no longer the crown jewel of his estate? Or that the Venetian merchant has so quickly shaken the grip of his old privations?

I can leave you no more, Your Eminence, save my word that these things are told in Venice, and that, in all humility, I have tried for nothing save a dependable summary,

Ever Yours, Most Faithfully,

BISHOP GUALTIERO GRIFFI

APPENDIX II

PHENOMENOLOGY OF THE SCREAMER

An essay by Giorgio De Maria

Translated by Ramon Glazov

[Translator’s Note: The term “screamer” in this piece is a literal rendering of the Italian urlatore—pl. urlatori—a wave of energetic pop-rock singers who emerged in Northern Italy at the start of the 1960s and have rough cousins in French yé-yé, the early Beatles and certain Jacques Brel tunes such as “Mathilde.”

Though 1960s jukebox hits seem mild compared to the rock genres that would succeed them, De Maria’s extraordinarily visceral analysis of the “screamer” phenomenon gives an early taste of the subjects that would obsess him in the darker period when he conceived The Twenty Days of Turin.]

In an interview with the singer Tony Dallara reproduced below,* we find certain statements that might provide an inroad to understanding the near-magical allure of the “screamer” ballad—an allure that has proven especially strong for the younger generations

.

Dallara, in short, doesn’t believe there’s anything new or surprising about the genre he is said to have “invented.” Youngsters like him were fed up with soppy tunes where they kept stumbling across the word “love” and the tears of rejected crooners. They demanded something else, something that agreed better with their youthful impulses. Dallara being, by his own definition, a “truthful” singer, incapable of affectation, did nothing more than listen to his instincts and take charge. The result was that his songs, almost by magic, seemed revolutionary: capable, that is, of quenching his unruly desires and those of his audience.

The conviction with which our singer-songwriter spoke about “sincerity,” with regards to his own way of doing things and to screamers in general, implied that this much-vaunted sincerity perhaps held the secret of the matter. And that his “taking charge” was little more than a better way to reveal and expose whatever still lay unexposed and unrevealed. Compared to his fellow screamers, then, the old crooners would seem like individuals trapped in a kind of melodious prudery. They were close to being hypocrites, never daring to express in plain words all the things that their songs implied.

From analyzing literary texts, we have seen how forcefully the element of narcissism appears in Italian popular music, blossoming from a state of near-endless frustration. So, to examine the screamers as the spiritual renovators of the Italian pop song, we need to consider the “scream factor” itself, endowed with powers that are unique in their own right, which the devotees of crooning had perhaps lacked. But it’s precisely this “scream factor” that leads us to suppose that if something new has happened in the music world, it’s not a case of evolution, but a regression to a psychological state that had already existed.

A scream, on its own—when it doesn’t indicate a genuine discovery of the world, full of childlike wonder—seldom means anything joyful. The voices within the song, high-pitched and strident, are often a musical emblem of pain. The musicologist Alan Lomax noted this studying the voices of Mediterranean folksingers from Spain and Southern Italy†—regions saddled with strong sexual repression. While the songs of northern peoples (referring, of course, to traditional works and not commercial pop) lean toward deep voices and relaxed melodies, in southern cultures the anguish of repression manifests itself in songs that are strident with frequent wailing. If the cause for our own screamers’ anguish is found in the lifestyle imposed by Northern Italy’s industrialized society, rather than in the moral traditions of the peasant south, we still can’t deny that a similar agitation exists deep within them. And perhaps the following passage from Lomax could be said just as well for the disciples of Adriano Celentano and Tony Dallara:

The day we fully learn the relationship between the vocal means essential to the expression of the emotions and how these connect to styles of singing, another big step will have been made in the field of scientific musicology. But in this particular case—regarding vocalists in Southern Italy—a few preliminary observations can be shared with the reader. When a human being lapses into an outburst of intense pain, it emits a series of sustained, doleful notes in an extremely shrill voice.

Grown adults too, just like children, scream in pain. To do this, the head is cast back and the jaw thrust forward; the soft palate draws near to the throat; the uvula tightens so that a small stream of air bursts out at high pressure to the top, vibrating the hard palate and the sinus. An easy try-at-home experiment ought to convince anyone that this is the best way to scream or moan. If, in the midst of it, you should open your eyes slightly (because if you’ve tried following my instructions they will be closed automatically) you will see your brow furrowed, your face and neck reddened, the facial muscles under your eyes pinched tight and your throat stretched by the effort.

The lyrics of screamer songs, those composed at least when the trend had already made its mark on sales, reveal their emotional origin clearly enough. Such goes for the song “Hate” [“L’odio”], which could well be considered the “Manifesto of Screamerism”:

Hate is all that burns in my heart,

After the love comes the hate!

[. . .]

(FROM “L’ODIO” BY U. BINDI/G. CALABRESE)

And much of that negative tension remains unaltered, even when the language being hurled about is otherwise tender. Such is the case with the Domenico Modugno song “Millions of Sparks” [“Milioni di scintille”], where the lover, having erupted into a flurry of schizoid imagery all because his favorite girl told him yes, overwhelms his song with repetitions of, “She said yes! She said yes! She said yes!” which are gradually lost in a limbo of onanistic desperation.

While in old crooner songs the “smoldering desire” was often veiled in allegory and softened by the melody, the new screamer compositions announce it in more explicit terms. “I want you, I want you, I want only you,” the rumba-rocker sings. “It’s you I want,” and he adds: “The joy, the agony, the fever—my desire for you is burning—because I want you—I want you to be mine.” The singer never happens to reach the object of his yearnings, but the song finally quietens into satiety. The bowstring of desire tenses back almost to the brink of snapping, and that’s where it stays, showing the lover caught in the throes of his spasm, yet perversely happy to display his state to others.

The typical fan of this genre isn’t content to hear it at a normal sound level. Rather, he feels a need to raise the speaker volume to its maximum limits, as if hoping to remove every obstacle between himself and the screamer. His is not the attitude of a person who listens to music and contemplates it, but of someone who immerses himself physically in its element and yearns to form a part of it. The screamer, with his anonymous spasms, is the listener himself with his indiscriminate sexuality; the effrontery of the voices erupting from the jukebox is the same effrontery as the listener’s, who, by virtue of the example he has been given, can finally shed the veils of his modesty. It might be said that screamer songs allow their audiences to strip bare while remaining clothed, to taste all the sordid thrills of carnal exhibitionism without officially crossing the line. It is, indeed, a kind of sanctioned transgression. The fact then that we are dealing not with an open, freely vented sexuality, but a repressed, wishful desire, reveals precisely the vocal style used by the screamers: intense, almost strangled at birth, as if a contradictory force were preventing it from expanding according to its natural cadence. It is here that we find a “sincere” rejection of the non-spontaneous.

And yet the songs scream, which—more than in any other popular music today—prompts the thought of an inward petrification, a coagulating interior, sometimes following the path of a rhythmic scheme that might even carry more than just a vocal or muscular spasm. Examining the lyrics of some of the latest songs in the genre, we could say that there is at least the attempt to exorcise the petrification, to escape it somehow. And here lies an ominously amusing side to the screamers.

Let’s take the example of a successful “cha-cha-cha” song, “When the Moon is Full” (“Quando c’è la luna piena,” A. De Lorenzo/G. Malgoni). We can observe three new features that contrast with tunes from the so-called “melodistic” or crooner repertoire: (1) the abolition of the chorus, (2) the lack of rests or pauses in the melodic pattern, (3) the stream of notes almost hitting back at each other, or at least with minimal space between them.

What should we read from innovations like these? What are the screamers aspiring for in their displays of rhythm? The recurrence of rhythmic sounds, duplicated obsessively and at length, have a noted effect on human beings. In his book The Story of Jazz, critic Marshall Stearns describes how during a visit to Haiti he had the good fortune of attending a primeval ceremony where:

For three or more hours, the housnis, or priestesses, danced and sang a regular response to the houngan’s cries, while the drum trio pounded away hypnotically. In a back room was an oven-like altar. Within the oven was a tank of water containing a snake, sacred to Damballa, and on top of this

altar was a second, smaller one, containing a blonde baby doll of the Coney Island variety and a statuette of the Madonna, twin symbols of Ezulie, goddess of fertility and chastity.

About eleven o’clock the lid blew off. Drinking from a paper-wrapped bottle, the houngan sprayed some liquid out of his mouth in a fine mist and the mambos, or women dancers, became seized with religious hysteria, or “possessed,” much like an epileptic fit. The rest of the group kept the “possessed” ones from hurting themselves. I saw one young and stately priestess, who had earlier impressed me with the poise and dignity of her dancing, bumping across the dirt floor in time with the drums. The spirit of Damballa, the snake god, had entered her.‡

Most likely, the screamers also hope to attain this kind of “possession,” an epileptic seizure that would at last free them from their possibly unbearable emotive tension. Except that their final payoff is nipped in the bud. The screamer indeed follows—if only to a modest extent—a pattern common to certain primordial ceremonies (of which Marshall Stearns’s account might serve as a textbook case). But instead of patiently waiting for the convulsive, liberating phenomenon to display itself, the screamer forestalls it from the first beat, leading to a self-denial of his only remaining outlet. Anyone who has seen Adriano Celentano in performance will recall the muscular spasms that alter his face and persona completely when he sings. He perfectly mimics the early warning signs of a seizure, though the actual attack never arrives, but lasts it out, so to speak, in a dormant cramplike condition. The screamer would like to take a sort of revenge against the industrialized society by regressing, at least in his intentions, to a primitive state. That “noble savage,” however, that he wants to reawaken in himself comes to life with all the neurotic symptoms of modern man—incapable, by his very alienation, of true spontaneity. And out of this comes the tragic fixity of the screamer’s song.

The Twenty Days of Turin

The Twenty Days of Turin